JVDW Gallery, Düsseldorf, 2025

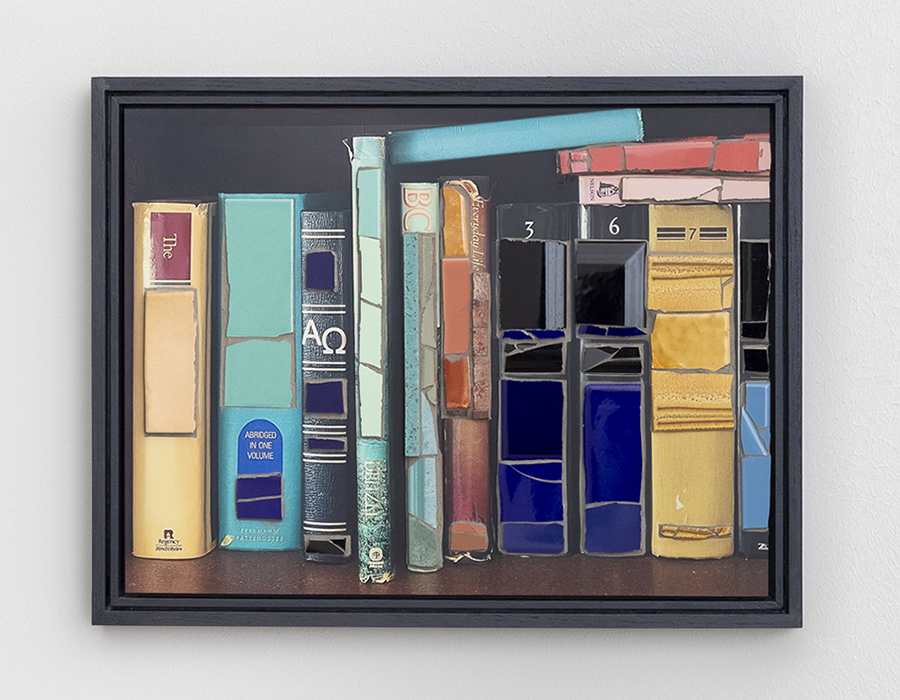

In his first show ‘Cool Vanilla’ at JVDW gallery, Stephen Kent presents viewers with a contemporary iconography of everyday artefacts rendered in different forms. Selectively scanned magazine fragments are turned into oversized prints on canvas. Quotidian objects are collected and cast into ceramic sculptures. And a series of assemblages are created through the collaging of tiles and mosaic stones within images drawn from his camera roll. These reproductions of inanimate objects are then brought together by Kent in the gallery to form a deconstructed, walk-through still life. Art history hasn’t always looked upon the everyday or mundane, and its reproduction within artworks, with the same admiration or esteem that Kent does.

In past centuries, the visual arts were dominated (perhaps tediously) by a strict hierarchy. History painting towered above the rest – ingrained with haughty, classical ideals, it was argued that these grand scenes, which typically depicted biblical scenes, mythological tales or significant historic events, allowed the great painters to express their craft to the fullest. Resolutely at the bottom of the pile lay still life – its immense shame being its humble desire to reproduce inanimate objects in a mechanical way. Over time, however, notions of taste and value (thankfully) change. During the Dutch Golden age, for instance, growing purchasing power, and a desire to show off this new wealth, led to an explosion in the popularity of still life paintings, as they captured the trappings of commercial abundance.

And roughly three centuries later, Dada and the readymade totally upended the hitherto entrenched values associated with the ‘fine’ art object. This shift away from rigid hierarchies, and the demolition of the boundaries between what has historically been regarded as high or low visual culture, invites the question: is there, in the end, any real difference in meaning between a 17th century Dutch painting that immortalizes the accoutrements of wealth and taste and an image taken from the pages of Schöner Wohnen? Or, is a classical Greek sculpture an inherently more successful or worthy repository of human culture than, say, a Labubu? The tearing down of canonical distinctions between high and low is fundamental to Kent’s practice. He centres and extols the mundane, confronting us with the often overlooked significance of the quotidian. In an apparent contradiction that is reflected in the exhibition’s seemingly oxymoronic title, the objects Kent depicts are somehow simultaneously ordinary (vanilla) and extraordinary (cool). Writing for the catalogue for the exhibition Die Schönheit der Dinge, which took place at Kunsthalle Emden in 2024, Kent stated: ‘Objects are our idols, icons of our ever-changing systems of meaning and belief.’ And what we are presented with in Cool Vanilla is an assemblage of these object-idols. Through his work, Kent asks us to consider how we use everyday objects to create our own personal mythologies. The keys contained in Sundial 1 are a symbol of where we belong. The nail polish ties its wearer to certain trends and brands, or the celebrities that endorse them. Bookshelves, such as the ones in Everyday Life, are symbols of the ideas we believe we value. And images from ideal living magazines allow us to project, to ourselves and others, how we would live if we could.

Text / Lincoln Dexter

Documentation / Alexander Mainusch

Typography / Massimiliano Audretsch